There's blood on my mosquito net

Sam Bankman-Fried was a rather poor spokesperson for the Effective Altruism movement. He defrauded investors who didn't realise they were investors en masse, presumably under a utilitarian extremist pretence. E.g., "if I could flip a weighted coin that had a 49% chance of tails and 51% chance of heads, I ought to flip it, regardless of fail case costs". Model it all you will and season with as many Pascal mugging variants as desired: the consequence was extraordinary human suffering.

I nevertheless believe the core tenets conceptualised by Peter Singer all those decades ago remain true: maximise "good" under resource constraints, wherever and whenever people might be suffering most. Compassion ought not be localised.

There are controversial "goods" and uncontroversial ones. For instance, there are doubtless many who believe shareholder value maximisation or exploiting market inefficiencies constitutes divine price setting, acts of pure benevolence with no relation to profit motives. A less contentious good would be saving lives, or maximising quality life years, where "quality" would be freedom from illness, harm and other worldly ills, or the alleviation of those that were unpreventable. This is typically the "good" I gravitate toward, as it requires less foreplay. If our goal is to maximise The Good, it's most expeditious to start with the uncontroversial sort for practical reasons in the first instance, and a lessened worldview misalignment hazard in the second.

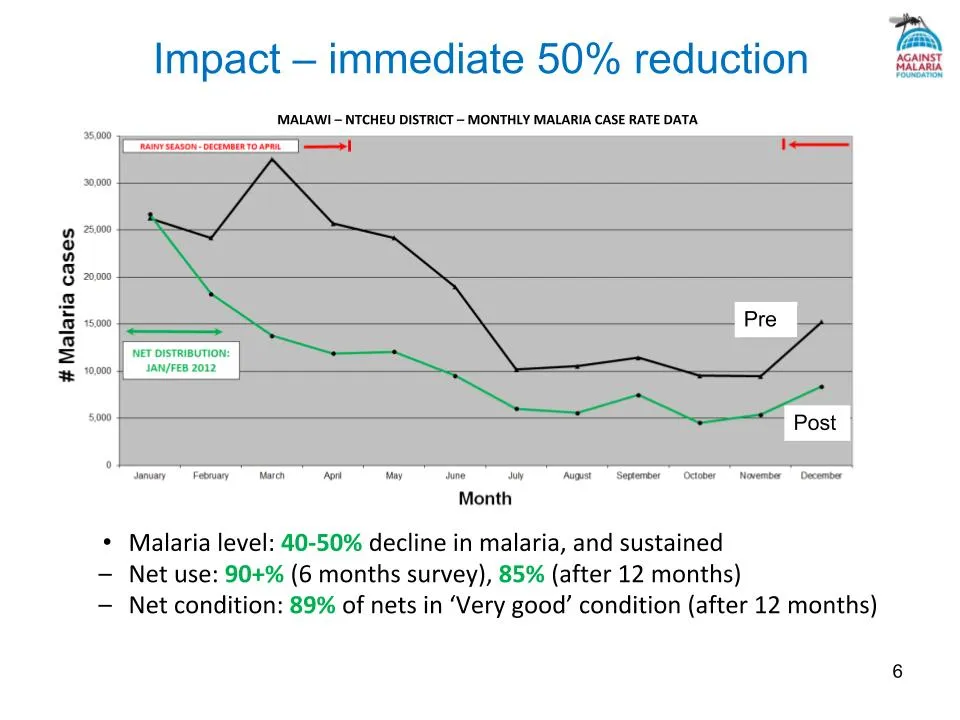

The "mosquito net" referenced in the title of this post refers to a famous cost-benefit analysis done by the Against Malaria Foundation years ago, finding them to be extraordinarily efficient on these "quality adjusted life years" terms. For $2 USD, at the time of the study, it was possible to buy a mosquito net in Sub-Saharan Africa (where 90% of mosquito-born harm was being inflicted). The net would cover two people, protecting them during mosquito prime time of 10pm to 2am. When the Foundation decided to distribute nets and educate locals, the results were staggering, and didn't seem to carry significant diminishing returns relative to other initiatives on similar time frames.

With this context in your hot little hand, know that when I refer to "mosquito nets", what I actually mean is "any linear, scaleable, high-impact for the cost way to save or improve lives".

One thing I've always struggled with, despite my belief in Effective Altruism the principle if not the movement, is the extent to which one ought to chase mosquito nets. It seems as though the most appealing strategy for an individual is to find them. But let's say we got drunk, hit the clubs one night, and woke up in the morning with a copy of Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals smoking in bed beside us. We might find ourselves compelled to universalise this principle. What if everyone targeted mosquito nets? The first order consequence would be saturation of various mosquito nets known to exist and desaturation of all others, such as toy distribution for children with fatal illnesses, or dog shelters. The second order might be a return to form, but more likely either a continued focus on high-impact initiatives up until the linear trend planks, or a diversion to the next most netty mosquito nets. I've therefore long seen effective giving in the developing world as something of a fraught principle. I want to maximise good, so I want to do all my charitable giving in the developing world, because that tends to be where you get the most bang (quality adjusted life years) for your buck (bucks, time, and other resources). Furthermore, I have no expectation of cause saturation owing to every living human focus-firing mosquito nets. At best, perhaps I can convince a handful of well-to-do first-worlders to part with some coin, but this theoretical hazard will never come to pass. Yet, I'd be advocating for something which I know is harmful if universalised.

One counter argument to this is possibly: what's so wrong with the most dire causes being given all the funding if they are indeed the most dire by the greatest extent, and further stand to benefit the most from this funding? I currently lean on worldview diversification as a response to this, however weak that may be. By this I mean: if you were to give all your money to a single cause, and some theoretical divine arbiter were to reveal with the light of pure reason that you were wrong, you'll have given everything to a worthless, or perhaps even harmful cause. To "diversify" your worldview is to accept a possible, contrary version of reality to yours. A possible altruistic hedge against Effective Altruism being false despite your best analysis suggesting the opposite might be: 8% of your income goes to mosquito nets, and 2% to something like a local homeless shelter. Yes, by all mathematical modelling, the nets might win by a long shot. But what if the modelling is wrong, or if Descartes's deceiving demon took a shit in your brain? At least you have 2% in the thank bank. That's worldview diversification.

Another struggle is at what point you start giving if you're an "earning to give" type person, as every dollar you give means a dollar you haven't invested to then earn more to give more later. Convoluted and hazardous reasoning, no doubt, but a nevertheless practical problem for the conscientious developed world-er.

The movement has historically regretted some of its marketing around this. In the early days, they were known for this principle: the notion that one ought to give X% of their income to charity. To their credit, they've only ever really advocated this as an option for people who can afford it; it being a focal point was only ever a media contrivance. Regardless, it is something they still advocate for provided you think it's your highest impact method of giving (relative to volunteering, setting up companies, running non profits, political lobbying and the like). So if you're in a highly paid career, perhaps hypothetically someone who worked for Jane Street and went on to set up a cryptocurrency trading platform worth billions, you might be tempted to keep banking and never cash out. I fortunately don't have the problem of billions of dollars, but I do have the problem of knowing how to scale giving with respect to the principles of worldview diversification and the hazards it seeks to avoid, a desire to maximise good through incremental donations, and a desire to not become Smaug.

I think the only real compromise here is to find a modest percentage distribution between classic investments and charitable ones, accept that you're a bag of fallible meat and deal with it, updating as and when new evidence arises that tickles your brain. As for the mosquito net problem, there are many organisations who specialise in researching high impact giving options, volunteering opportunities, jobs and such. I quite like 80,000 Hours for this.

Sam Bankman-Fried's story is tragic to me on two axes, and I can't stop thinking about either of them. First and foremost are the people he hurt: the ones who lost everything, and whose lives were irreparably damaged. But I also can't stop thinking about the people he could have helped had he just cashed out and not stolen from people. His organic, legitimate earnings were in the billions; this gambit of defrauding people was just a play at more billions on the pile. Had he opted out of going the unethical route near the end, that could have been billions into cancer research, climate change advocacy, LGBTQIA+ rights, and of course a butt load of mosquito nets. Future generations of entire populations, cities, could have been lifted from poverty in the developed world, and their children, with increased nutrition, education and opportunities, would have went on to have well-nourished, educated, safe and loved children of their own. His misaligned, all-in, unhedged worldview cost the lives of potentially millions of happy, healthy people that will now never exist to propagate into the future. Eliezer Yudkowsky cornered him in a darkened alley, and Sam gave up everything without even seeing the knife.

I will never be a billionaire, but I at least aspire to do as much as I can with the little I have. It might mean mosquito nets, but it might also be soup kitchens. I aspire to have modesty, to not justify moral decisions with immoral actions, and to look sceptically at weighted coins.